Genocide denial in Guatemala - ‘Memory battles’ in Guatemala, and in the U.S. and the West

Below, we share a NACLA article about Guatemala’s ongoing memory battles related to the country-wide massacres and disappearances, and genocides in four particular Maya regions, that were at their worst in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since 2016, these battles have become all the more difficult again as the traditional economic, military and political elites – known as the Pact of the Corrupt – have pushed back violently and corruptly.

These “memory battles” in Guatemala belong equally in the U.S. and the West, particularly Britain, France, Germany and Israel.

The U.S. has long illegally exerted its economic, military, political and informational (ideological) power across the Americas, as it is doing today ‘on steroids’, and very violently in Venezuela and Cuba.

During the worst years of extreme State violence in Central America in the late 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. brought in these key allies, and some others, to help provide weapons, training and ‘boots on the ground’ support to military regimes in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, and to the U.S.-Contra forces trying to crush the hated ‘Sandinista’ government of Nicaragua.

Since these worst years of genocide and slaughter, there has been a little to no justice achieved in Central America, and – sadly, as usual - absolutely no legal or political accounting for the fully complicity of the U.S. and key Western allies.

Guatemala’s Ongoing Memory Battles

For over ten years, Angélica Macario has sought to preserve the archive of the Council for Ethnic Community Runujel Junam (CERJ) in a struggle to keep the memory of the genocide alive.

By Emily Taylor, & Angélica Macario, NACLA, February 17, 2026

https://nacla.org/guatemalas-ongoing-memory-battles/

Angélica Macario attends a meeting with women. (Credit: Angélica Macario)

As a human rights activist, Angélica Macario was used to the hubbub and noise of protests and to seeing her people take their clamor for justice from the mountains of El Quiché to the streets of Guatemala City. For the past 20 years, however, she has carried on that legacy in another way—one which began with her father and dozens of other community activists in the 1980s.

Since 2003, she has safeguarded the archives of las Comunidades Étnicas Runujel Junam (Council for Ethnic Community Runujel Junam, CERJ), a community organization founded in 1988 to resist state-sponsored genocide.

Ángelica grew up in Chulumal Cuarto, an aldea of Chichicastenango in the highland department of El Quiché. At the time, the department was the center of a brutal state-backed counterinsurgency. According to the UN-sponsored truth commission report, Memory of Silence, there were more than 344 massacres in El Quiché and that 45 percent of human rights abuses occurred in the department during the 36-year conflict.

Memory of Silence also reports that more than 200,000 civilians were killed and more than 1 million displaced between 1960 and 1996—almost entirely at the hands of state agents—and found that the state of Guatemala had committed genocide against Indigenous Maya groups.

The CERJ archive tells the story of Maya resistance to this state-sponsored genocide in more than 80 boxes (more than 75 linear feet) of meeting minutes, police reports, flyers, and pamphlets. Together, the archive documents the group’s efforts to bring democracy to Guatemala, exhume clandestine cemeteries, and to deliver direct aid to the survivors of genocidal violence.

Now, Angelica and her compañeros are processing and digitizing the CERJ Historical Archive to rescue and preserve the group’s legacy and carry on the fight for historical memory and social justice in Guatemala despite institutional and personal obstacles.

Indigenous Resistance to Dictatorship

The CERJ archive tells the story of Maya resistance to this state-sponsored genocide in more than 80 boxes of meeting minutes, police reports, flyers, and pamphlets.

Angelica grew up steeped in the tradition of Indigenous resistance and community resilience. As a child, she attended CERJ meetings and protests alongside her father, Don Eusebio Macario. They were protesting the actions of the state backed counterinsurgency, known as the Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil, or Civil Defense Patrols (PACs).

The PACs were created by Generals Lucas García and Ríos Montt in the early 1980s to combat the country’s insurgent movements. However, they soon became a key mechanism of genocide.

Military leaders forced all Indigenous men between the ages of 15 and 65 to participate in weekly, 24-hour shifts patrolling the countryside for so-called “subversives,” which the military broadly defined as anyone from guerrilla members, Catholic catechists, cooperative leaders, and eventually entire ethnic groups.

Under threat from military commissioners, community members were forced to torture and murder their neighbors and family members; declining to participate in the supposedly voluntary patrols resulted in suspicion of subversive leanings or even immediate execution.

As a response, in the late 1980s, Don Eusebio co-founded CERJ alongside other K’iche’ Maya community leaders to oppose the PACs, organizing protests and marches at a time when the state did not tolerate opposition activities of any kind.

CERJ worked alongside partner organizations like the Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo (GAM) and the Coordinador Nacional de Viudas de Guatemala (CONAVIGUA) to re-open civil society and demand that the state be held accountable for its crimes. CERJ leaders and members were constantly surveilled and threatened by state agents; in 1989, CERJ members Agapito Pérez Lucas, Nicolás Mateo, Macario Pú Chivalán, and Luis Ruiz Luis were kidnapped and disappeared by state agents.

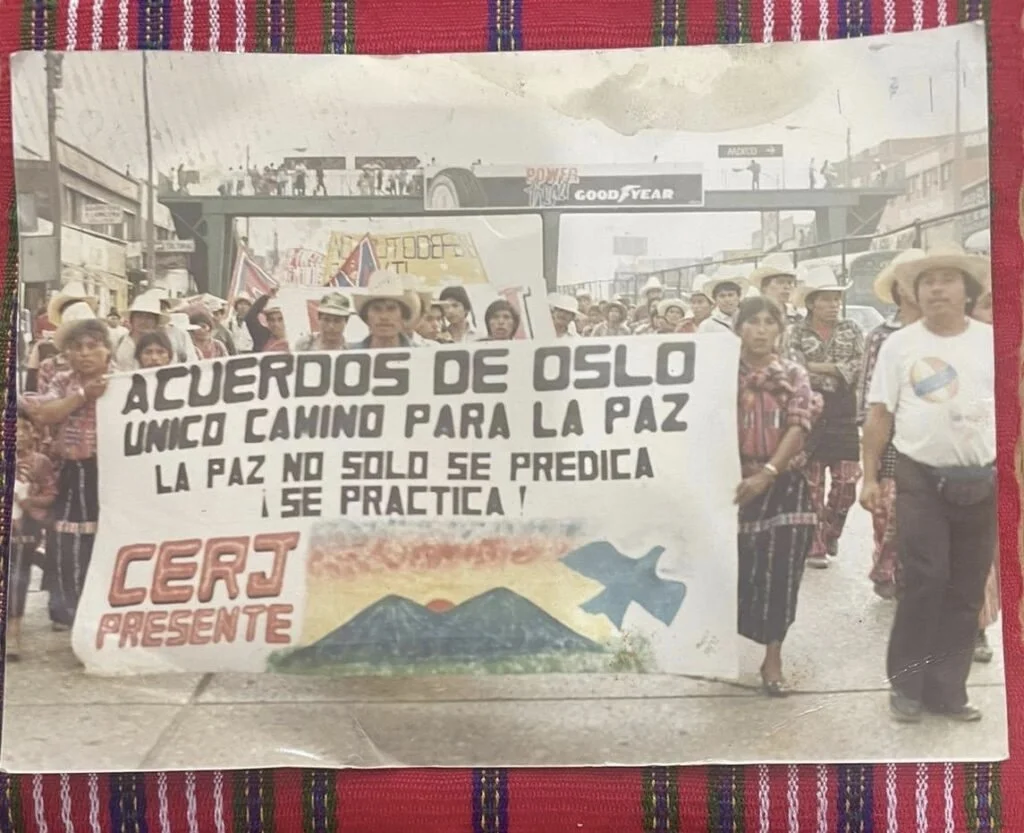

CERJ protest in the 1990s. (Credit: Amílcar Mendez)

Human rights advocate Amílcar Mendes worked alongside Don Eusebio Macario to found and lead the organization. Don Amílcar recently explained: “CERJ was a kind of human rights defense for Indigenous communities, who were the population that truly suffered during the armed conflict.” He continued, “CERJ arose from a great need; [it was] born out of the fear and terror they were experiencing. They wanted to defend themselves somehow.”

With other CERJ leaders, they were recognized for their important human rights work by the Robert F. Kennedy Center as well by the Carter-Menil Human Rights Award.

After the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996, CERJ continued working to procure reparations for survivors of the genocide and to protest ongoing human rights violations.

The signing of the Accords, however, did not bring peace. On September 27, 2003, Don Eusebio was assassinated by former PAC leaders who were allegedly associated with Ríos Montt’s political party, the Frente Republicano Guatemalteco. Amnesty International reported that he had received threats before his death and published an urgent alert for the safety of Angelica, Don Amílcar, and other CERJ members.

In the wake of Don Eusebio’s assasination, the CERJ closed their office and Angelica took possession of the archive. Today, Don Amílcar continues to fight for justice for his compañeros through the legal system, including through ongoing cases in front of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR).

In November 2024, the IACHR found the Guatemalan state guilty of forcibly disappearing four CERJ leaders in 1989. In a ceremony in the National palace in December 2025, President Arévalo formally apologized for the disappearances.

Continuing the Fight

For Angelica, her ongoing struggle for justice and accountability honors her father’s memory.

Since 2003, Angelica has worked with community members and friendly NGOs to preserve the CERJ’s archive.

“I was conscious of what the organization had, of what the documents were. That they could be useful for the next generation to come, who don’t know what we have gone through,” she said. “I realized that even teachers didn’t tell these stories, unlike in my house where we talk about everything that has happened in this country,” she added.

Marcia Esparza, Associate Professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, has helped her in these efforts. Dr. Esparza, who works on historical memory, lauded the importance of the archive.“ They are a testimony that the army carried out genocide,” she said. Dr. Esparza is also in the process of writing a children’s book called “La Historia de Angélica” or “Angelica’s Story,” to teach future generations about the internal conflict and Indigenous communities’ struggles for justice.

After many years of shuffling between cramped spare rooms and damp garages, the archive is now located within the offices of a well-known human rights organization in Guatemala. While not permanent, this stability has allowed the team to begin the arduous work of organizing, preserving, and digitizing this vital piece of Guatemalan history.

In 2024, the CERJ Archive team along with the Swiss Peace Foundation were awarded an Endangered Archives Grant from UCLA to finance the organization and digitization of the archive. They hope to make these valuable documents available to survivors of the genocide, academics, and future generations of Guatemalans who are interested in learning about the Internal Armed Conflict, the peace process, human rights, Indigenous and campesino resistance, and state-sponsored human rights violations in Guatemala.

Historical Memory in Guatemala

The efforts of the CERJ Archive have been particularly timely. After the 2005 discovery of the Archivo Histórico de la Polícia Nacional (AHPN) in an abandoned building on a police base in Guatemala City, which contained millions of pages of vital evidence on state crimes during the internal conflict, activists successfully fought for their preservation and use in prosecutions of human rights abuses.

These records were essential evidence in successful convictions of former high-ranking military leaders like former army chief of staff Benedicto Lucas García.

However, in recent years, the AHPN has been all but silenced; a military-led takeover of the archive in 2018 led to the dismissal of the majority of the staff and the de-facto closure of the collection to researchers and activists.

Alongside other concerning developments like the prosecution and incarceration of journalist José Rubén Zamora, the repression of the AHPN has become indicative of what many observers have lamented as the retreat of historical memory efforts in the country.

In the face of the AHPN’s retreat, the CERJ Archive hopes to carry on the legacy of AHPN. In fact, three of the four CERJ Archive staff started at AHPN. For Ana Virginia Lucero, one of those staffers, “the AHPN was a training ground for specialists in human rights archives.” The closing down of the AHPN archive, she said, is being filled by others like the CERJ historical archive.

CERJ archive technical team. (Photo: Angélica Macario)

The difficulties encountered by the CERJ archive come in some ways at a surprising time: for the first time in decades, the country is ruled by a progressive government. In 2023, center-left deputy Bernardo Arévalo, won the presidency in one of the most surprising electoral victories in recent memory. While his administration has made some important gestures towards righting historic wrongs, he has been continually hamstrung by the Attorney General Consuelo Porras’ ongoing attacks against democratic processes and structures.

Since taking office in May 2018 and winning re-election in 2022, Porras has targeted institutions like the AHPN for investigation and prosecution, facilitating the military take-over of the human rights archive. This ongoing threat looms over human rights activists and institutions despite Arévalo’s continued efforts.

The process to name the next Attorney General is due to conclude in the coming months but the results are far from certain, leaving the CERJ archive and their allies vulnerable.

Within this context, the archive has continued to face intimidation and financial difficulties. Another Endangered Archives Grantee, The Human Rights Office of the Archbishop of Guatemala, was raided and ransacked by unknown actors in February 2024, sending a chilling message to the entire human rights community in the aftermath of Arévalo’s inauguration.

Angelica, however, is no stranger to threats herself. In 2008, she survived an attempted lynching when she was assisting with an exhumation of victims of the armed conflict in Chichicastenango. Despite all this, she has continued to advocate for the archive and for the preservation of historical memory in Guatemala.

Alongside other CERJ Archive staffers, Angelica continues to fight for justice for her father and other victims of the internal armed conflict. “Despite everything that I’ve lived through, I haven’t stopped fighting, because even though they are difficult experiences, at the same time it is really beautiful to be able to help your neighbors,” she said.

The CERJ Archive is open for researchers, human rights activists, and survivors of the genocide. They can be reached at cerj.2023@hotmail.com.

(Emily Taylor is a PhD candidate in Latin American History at UNC Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on citizenship struggles and gender in 20th century Guatemala. Angélica Macario is a K’iche’ Maya human rights activist based between Chichicastenango and Guatemala City.)

Since 1995, Rights Action has supported and reported on many ‘truth, memory, justice’ struggles, most particularly in the Maya Achi region centered in Rabinal, Baja Verapaz, to the west of Quiche.

Change media sources

Rights Action urges folks to diversify their news sources as an antidote to the oftentimes misleading reporting coming from much of the government and corporate media in the U.S. and Canada. We recommend The Gray Zone, Democracy Now, DropSite News, The Real News Network, CounterPunch, The Intercept, Canadian Foreign Policy Institute, The Breach, rabble.ca, Orinoco Tribune, Al Jazeera News (coverage of Palestine), …